BioTIME Blog

Introducing BioTIME Trinidad

The rainforest-covered mountains of a Caribbean island are the location of the BioTIME Trinidad project. Here, the numerous parallel streams of Trinidad’s Northern Range provide an ideal ‘natural laboratory’ for investigating patterns of biodiversity over time.

As a post-doc on the project, my job includes coordinating the data collection and managing an enthusiastic team of field and lab assistants – as well as many hours wading through some of the most (and least!) beautiful streams on the island.

We will soon be entering the final year of this exciting 5 year project. Through this blog, I hope to write about some of the adventures we have in the field and highlight any interesting discoveries we make along the way…

May 2014

Dry season sampling – complete!

Avinash Deonarinesingh, Raj Mahabir, Kharran Deonarinesingh, Devan Inderlall

An especially cheerful BioTIME Trinidad fieldwork team having just completed the final survey of the session, at the beautiful Acono river. This session has coincided with the dry season, and water levels have been noticeably lower. Seasonal differences such as this can also affect patterns of biodiversity over time, which is the focus of the BioTIME project. The next set of surveys will begin in August, by which time the rains will have returned.

Avinash Deonarinesingh, Raj Mahabir, Kharran Deonarinesingh, Amy Deacon

August 2014

Rain in the rainforest and pseudoscorpions in our samples…

Trinidad’s tropical climate consists of a dry season and a rainy season. Our August sampling session falls in the middle of the rainy season, which this year certainly lived up to its name. Miraculously, we managed to avoid postponing or abandoning any sampling sessions, despite getting completely drenched on several occasions.

It is times like this that I am thankful for my waterproof field notebook, but even more so for my dedicated field colleagues Raj, Kharran and Avinash, who manage to keep their sense of humour even when attempting to shelter under futile banana-leaf umbrellas with cold rain trickling down their backs. When you are soaked to the skin, even tropical Trinidad can feel cold…

Meanwhile, back on campus, BioTIME research assistant Devan has been making some exciting discoveries in the laboratory. While sorting through the benthic samples from the April-May session he came across our first pseudoscorpion! This tiny arachnid looks just like a scorpion but without the sting in the tail (although many have venom glands on their pedipalps instead), and is typically found in leaf-litter on the forest floor. There are 16 species recorded from Trinidad, but none are aquatic so this one most likely fell into one of our sample zones from the riverbank. We find a great diversity of creatures in these samples, from fierce-looking dragonfly larvae to limpet-like water pennies, and it is always exciting to find something new.

Our next sampling will take place in October, and will mark the start of the project’s final year. In the meantime Devan and I will be in the nice, dry lab, continuing to process the invertebrate and diatom samples that we have collected this summer. Who knows what we might find…

Species Profile

Jumbie teta: a fish possessed?

We find many different species of fish across our study sites, of all shapes, sizes and habits. One of the most bizarre is the armoured Ancistrus maracasae, known locally as ‘jumbie teta’. This species is endemic to Trinidad and named after the Maracas River, from which the first type specimen was described. ‘Jumbie’ is the Trinidadian word for evil spirit or demon, and the dark body and grotesque appearance of this fish is probably how it earned its local name.

Personally, I don’t find it ugly at all – in my opinion the elaborate fleshy facial protrusions (which are more pronounced on the males) only add character to this prehistoric-looking bottom-dweller, making it one of my favourites.

September 2014

Musical diatoms

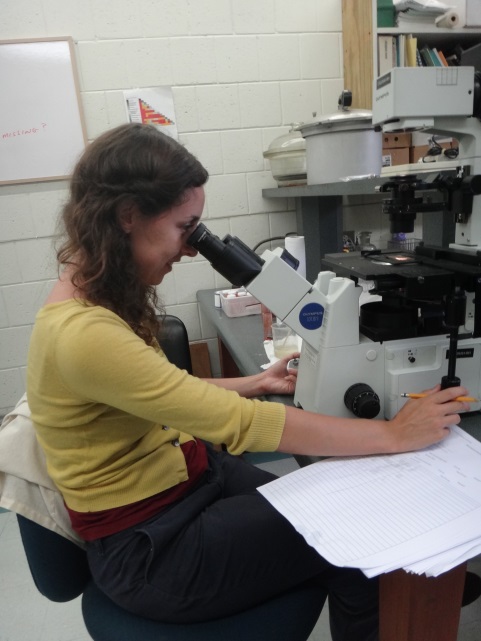

Although I love spending time in the rainforest and getting my feet wet in mountain streams, equally important is the processing of samples we collect.

I spend a significant amount of my time counting microscopic diatoms in the laboratory. These single-celled algae with silica shells (‘frustules’) are abundant in streams all over the world and as photosynthetic organisms, are vital primary producers in river ecosystems.

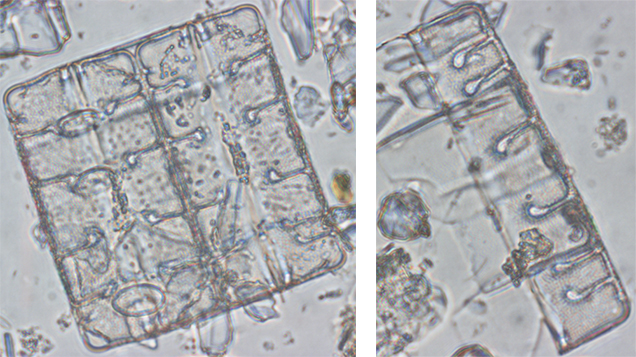

Diatoms vary enormously in form – common shapes include ‘S’-shaped, spherical, elongated, lemon-shaped and diamond. This morphological diversity makes it possible, if not easy, for different types to be identified. One of my favourites is Terpsinöe musica – named after the ‘crotchets’ that are visible inside the frustule.

We find many thousands of diatoms on every small rock that we sample. Knowing that this work will help reveal some of the secrets of a whole living community that is usually invisible to us, makes all those hours at the microscope worthwhile!

Species Profile

The snail-case caddis and its helical home

From a distance they look like tiny snails, clinging to the underside of rocks. A closer look reveals that their perfect spirals are in fact made up of hundreds of grains of coarse sand. An even closer look and a little head and a pair of legs might appear – and it becomes clear that these are the homes of tiny aquatic insects!

More precisely, they belong to caddisfly larvae of the genus Helicopsyche (family Helicopsychidae), otherwise known as the ‘snail-case’ caddises. Indeed, the resemblance is so strong that the first scientific description (based on the case alone) classified them as gastropod molluscs!

These miniature architects secrete silk from their salivary glands, which they use to bind the particles of sand and gravel together. Interestingly, the spiral is always constructed in a clockwise direction, and is usually less than 1cm in diameter.

Like many semi-aquatic insects, they spend most of their lives as larvae in the streams, emerging for just a few days or weeks as mature, winged adults in order to breed. As larvae they play an important role in the stream ecosystem as they graze diatoms and detritus from the rocks, and are in turn predated upon by other stream inhabitants.

As they tend to aggregate in large numbers, we sometimes find more than 100 snail-case caddises in just one sample. Those still inside their cases are easily identified, but in the absence of their characteristic helical home, it can be a great challenge!

October 2014

Chasing guppies

This week marks the start of a new survey season for the BioTIME team. Over the next four weeks we will return to each of our long-term river sites to monitor the communities of fish, invertebrates and algae that they support.

There is one species of fish we find without fail on every single one of our surveys: the Trinidadian guppy, Poecilia reticulata. We may find as few as seven, or as many as 1000 of these tiny fish at one site, using a combination of dip-netting and hand-seining. Catching them can be quite a challenge as they have evolved excellent predator evasion abilities that also apply to our nets!

Guppies are a vital component of the ecosystem as they feast on diatoms and invertebrates, while in turn being predated upon by the larger fish. They are small (2-4cm), reproduce incredibly quickly and are extremely adaptable to changing conditions; it is no wonder they have been studied so thoroughly by evolutionary ecologists here in the Northern Range!

Indeed, these remarkable little fish were the subject of my PhD thesis, the focus of which was their invasive success outside of Trinidad (with the help of humans, they are now established in at least 70 other countries around the world).

Having studied guppies for so long, I am very glad to still have the opportunity to encounter them regularly, albeit now exclusively in their native habitat!

November 2014

‘River limes’ and religious rituals

Yesterday, on arrival at one of our sites in the Maracas Valley, we discovered abundant evidence of Shouter Baptist rituals; colourful flags, candles, incense burners and food offerings were scattered around the site. Clearly this had been the venue for some elaborate ceremonies over the weekend.

People are attracted to water, and recreational use is something that affects rivers worldwide.

In Trinidad, the ‘river lime’ – families and friends meeting by the river for eating, drinking, bathing and socialising – is a cultural phenomenon. Every weekend and public holiday, certain river spots swarm with people enjoying the outdoors and beautiful scenery. Rivers are not purely social venues either, many local residents use them for everyday bathing and cooking.

Combined with different religious groups using freshwater habitats for their observances, the result is that some of our river sites are bustling hubs of human activity most days of the week – both in the water and on the riverbanks.

At least by completing our surveys as early in the morning as possible we are usually able to sample in peace, even if we are still greeted by large piles of garbage – and, on occasion, the carcasses of sacrificed goats…

We survey a wide range of sites as part of the BioTIME study, including both disturbed sites like this one, as well others that are less commonly used by people. It is unclear exactly how, and to what extent, these kinds of human disturbances affect aquatic communities. Hopefully our data will offer some insights.

Species Profile

Jumping guabine: a fish out of water

The jumping guabine (Aneblepsoides hartii – formerly Rivulus hartii) is another of the species we find at most of our sites.

At full size, these fish are around 10cm with vivid horizontal coloured stripes stretching along their body. Males and females can be distinguished fairly easily by their colouration; males tend to be brighter and have distinctive pale orange edges to the tail, while the female’s tail has a darkened tip.

The jumping guabine is found throughout Trinidad and Tobago as well as in northern Venezuela. They thrive in a variety of habitats, from muddy road-side puddles to the shallow edges of large rivers.

As the name suggests, it has the ability to launch itself completely out of the water. The ability to beach yourself may not seem like much of an evolutionary advantage, but this fish has another trick up its sleeve – it can breathe atmospheric air through its tail, which is covered in capillaries. As such, a jumping guabine can jump out of water onto land and survive for a considerable time, as long as it does not dry out entirely.

This allows these fish to travel short distances over land to new bodies of water, and it is not unusual to find a few individuals in isolated puddles, often some distance away from permanent water. This is one of the reasons they are often the only fish found in the highest stretches of rivers in the northern range – pools that even guppies have failed to colonise. Jumping guabines can simply make multiple jumps to scale the sheer rock face of a waterfall!

Incredibly, they have been recorded jumping as high as 14cm, more than their total body length, to catch prey from the vegetation. While in the water, they are ravenous predators of small aquatic invertebrates, small fish and tadpoles.

Unlike guppies, jumping guabine don’t shoal for protection. Instead they have an incredibly quick escape response – indeed, often all you see is a flicker as they dart for cover on sensing your approach. There is a good reason for this reaction – as well as bird and fish predators, I recently witnessed a large spider (Dolomedes sp.) capture an adult jumping guabine from the water’s edge!

During fieldwork surveys the constant leaping provides us with a real challenge, especially when weighing each fish individually. The lesson: never underestimate the escape abilities of a jumping guabine!

November 2014

Challenging conditions and an exotic species

It is very unusual for us to have to abandon surveying due to the weather; thanks to our waterproof notebooks, we can work through moderate showers, or shelter for a while until heavier rain eases. However, this week things became too challenging even for us. Here is a photo of our Quare River site on Tuesday:

With the persistent, heavy rain, the water rapidly became opaque and fast-flowing, to the point that it was a challenge to stand up, let alone catch fish! As we waited in the hope that the weather would improve, instead the conditions continued to deteriorate. Cold and wet, we were forced to give up and return two days later for a second attempt.

As we embarked on the hour-long journey for the second time that week, we found ourselves driving towards ominous dark clouds; it did not look promising and I feared this would be another wasted trip. Miraculously, things brightened up as we approached the site – the river remained turbid and relatively fast flowing, but it was possible to safely complete the survey.

The physical effects of the heavy rain were clear to see, and extreme conditions like this undoubtedly affect the stream inhabitants. We have yet to examine the invertebrate and diatom samples, but it is already clear that the fish community was heavily impacted. The most noticeable difference was the dominance of an exotic species, tilapia (Oreochromis sp.), in our samples.

Tilapia originate from Africa, and tend to be introduced to ponds and lakes here in Trinidad for aquaculture purposes. It is rare to find this species in the fast-flowing stream habitats that we survey. However, for many years there has been an introduced population in the reservoir upstream of this particular site, and it is likely that some individuals were washed down by the strong currents.

It will be interesting to see what differences we detect in the other taxa, and whether the tilapia will persist in these lower reaches for longer than a few days or weeks.

January 2015

Another year, another sampling session begins!

This month BioTIME Principal Investigator Anne Magurran is visiting Trinidad, as she has done regularly for over twenty-five years now. Likewise, our UWI colleague Professor Indar Ramnarine welcomed the excuse of Anne’s visit to get away from his desk and back into the field, resulting in a full team at the Upper Aripo site today.

This site is one of my favourites – small waterfalls interspersed with riffles and pools, and lovely vegetation and birdlife.

We have now officially entered the dry season, but we experienced a couple of short showers this morning nonetheless – not enough to deter us, of course! We soon dried off and finished the survey, before stopping at Arima on the way home at our favourite Roti shop for a well-earned lunch…

February 2015

Damsels and dragons…

Damselflies and dragonflies (order: Odonata) are common at all of our sites, and although we don’t actually record the number of colourful adults that sun themselves on the riverbank vegetation, we DO count the numerous larvae that we find in our benthic samples. In fact, like caddisflies, damsels and dragons spend most of their lives underwater, emerging primarily to mate and lay eggs.

At least 120 species belonging to the Odonata can be found in Trinidad. My favourite is the ‘ornate helicopter’ (Mecistogaster ornata), which is a species of giant forest damselfly. These uniquely tropical insects can be as long as 10cm – with even larger wingspans. The name ‘helicopter’ comes from their distinctive flying style and their main prey is spiders, which they carefully pluck from webs as they ‘spin’ through the forest.

Last week, on visiting our Lower Aripo site, I noticed an empty dragonfly case on a half-submerged rock among the riffles. I soon realised that there were one or two on almost every other rock I examined – the larvae must have emerged in synchrony earlier that day. I found a damselfly case on a nearby leaf, too.

Having emerged from the water after many months, some species actually return to the underwater world for their final act; a couple of years ago, at our Quare site, we observed damselflies diving right down under the water to lay their eggs on submerged vegetation – quite amazing to witness.

Having a high diversity of damselfly and dragonfly species is sometimes thought to be a good indication of the health of a stream ecosystem – I wonder whether the benthic data will reveal any differences between our disturbed and undisturbed sites?

A day off: hiking in the Northern Range

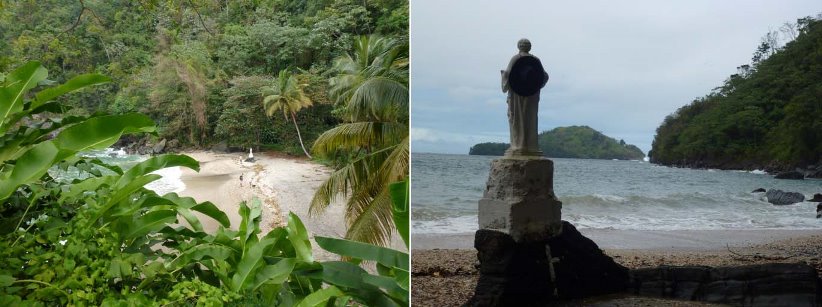

Last week we finally finished our last field site for the session. To celebrate, I spent my Sunday…in the field! Despite living in Trinidad for over 4 years now, there are still some hikes that I have yet to try, so I was excited when a friend suggested we attempt a new route in the north of the island – to the elusive St Cion Bay.

We began in cool, breezy hills at the western end of the Northern Range – near the village of Paramin, a farming community famous for music, blue devils and cool breezes.

Unfortunately the view from the ridge was non-existent as we were greeted by sheets of rain, even though March is traditionally one of the driest months here. This also meant that the downward hike was treacherous, with slippery rocks and leaves underfoot. We were forced to take a very slow pace, watching our every step – and even so, several of our party ended up on the ground at various points. Thankfully no serious injuries were sustained, and the forest in the misty rain was magical.

After a couple of hours, the rain stopped, just as we emerged from the forested slope onto an idyllic deserted bay; empty apart from an imposing white statue of St Peter, permanently cemented onto a rocky outcrop in the middle of the beach. This odd discovery only added to the feeling of adventure as we explored our new surroundings: waterfalls, strange rock formations, a palm fringed headland and a view straight out to the uninhabited Saut D’Eau island.

Soon we smelled that we were not alone – a huge dead tarpon (1.5m) lay in the tide line. Just as we were speculating on what might have killed such a big fish, we noticed a fully inflated spiny porcupine fish lodged in the tarpon’s mouth. It seems that this predator chose the wrong dinner – and the story didn’t end well for the tarpon or its prey.

After lunch, a few of us decided to scramble around the corner of the bay to find the waterfall that could be seen from afar, and to enjoy a refreshing shower.

The way back up the hill was less slippery, but hard work all the same. Thankfully the forest was full of distractions that acted as welcome excuses to stop and catch breath. First we spotted a ‘jep tatu’ wasp nest (Synoeca surinama), named because the nest resembles a tatu (the local name for armadillo). Luckily for us, the nest was high up a tree – as this species is known for possessing a particularly painful sting. Next, we found a friendlier bark mantid (Liturgusa trinidadensis). These masters of camouflage live on tree trunks, actively hunting for prey.

By now the clouds had lifted and we enjoyed some spectacular views looking back towards the sea.

On reaching the top, we were rewarded with panoramic views of the island. As I looked across at the layers of mountains to the east, I tried my best to identify the hills and valleys where our BioTIME streams lie…and was very grateful that my tired legs would not have to venture to them the following morning!

Species Profile

The cave-dwelling catfish, Rhamdia quelen

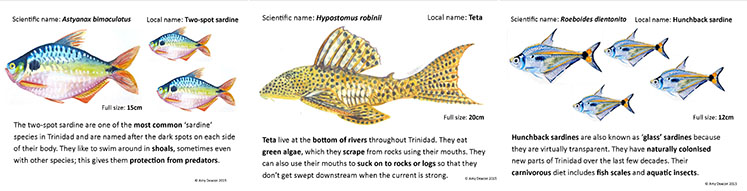

The rivers of Trinidad are home to six very distinctive types of catfish, five of which we find commonly at our BioTIME sites. These include armoured catfish such as the leopard-spotted ‘teta’ (Hypostomus robinii), the mysterious ‘jumbie teta’ (Ancistrus maracasae – see earlier post) and the popular aquarium fish ‘pui pui’ (Corydoras aeneus).

All tend to be bottom-dwellers and are grouped together as ‘cat’ fish on account of their barbels, which are sensory ‘whisker-like’ structures on their faces used to locate food. In Trinidad the fish most commonly referred to by the name ‘catfish’ is Rhamdia quelen, which unlike the species listed above, is silvery, unarmoured and scaleless.

Rhamdia is found throughout much of Central and South America, from Mexico to Argentina. In T&T, it is especially common in the rivers of the southern slopes of the Northern Range, but is found throughout the country, with the exception of Trinidad’s north coast and the whole of Tobago.

Like many catfish species, Rhamdia possess mildly venomous spiny rays on their pectoral and dorsal fins, which are used for defence against larger predatory fish. The barbels on either side of their face help them locate food in dark or murky waters, such as their preferred prey of small fish. However, their varied omnivorous diet also includes insects, zooplankton, plant matter and crustaceans.

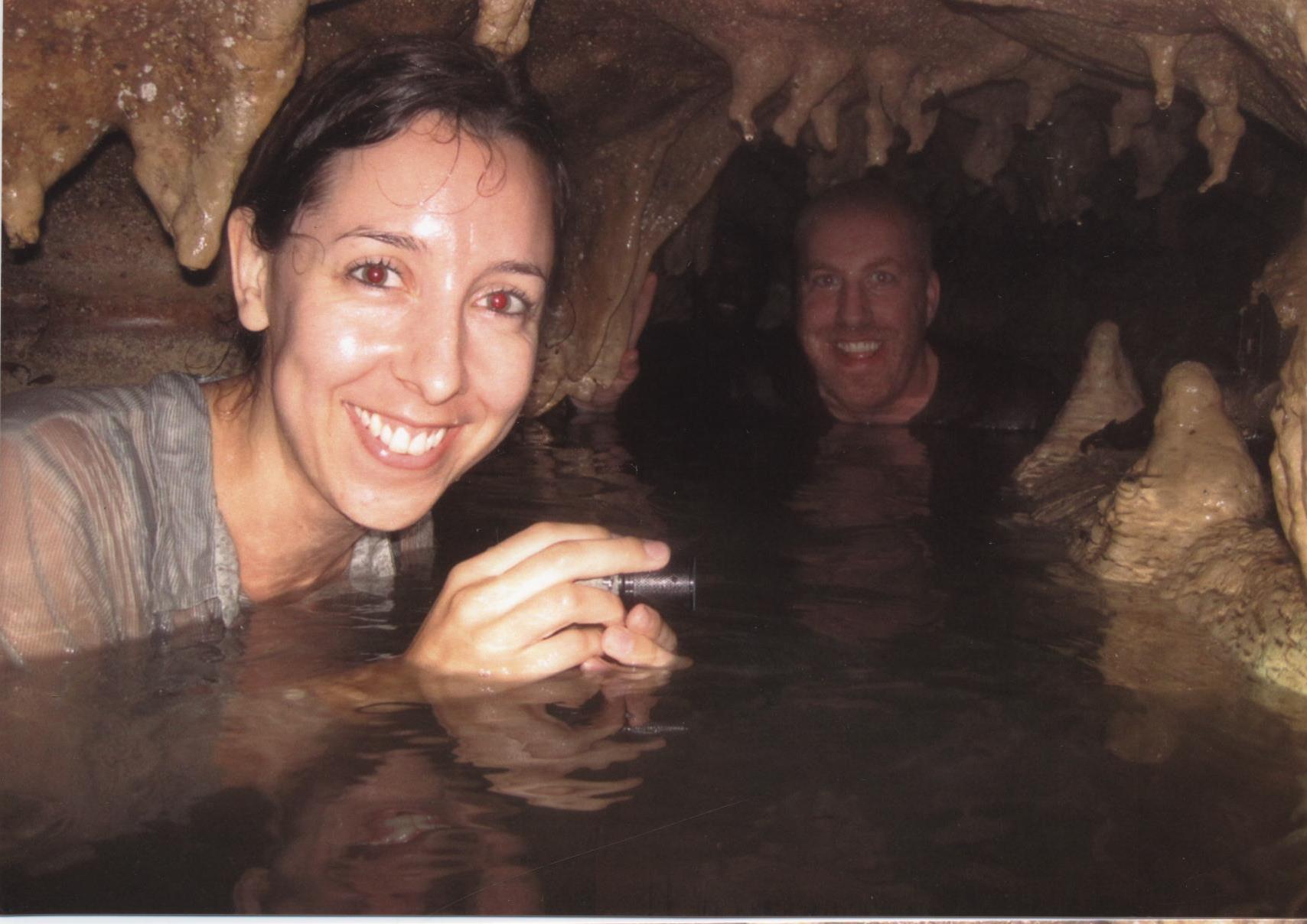

Rhamdia especially favour the shadowy waters underneath bridges. They tend to hide under rocks or dead wood during the day, emerging into the open at night to feed. Incredibly, one population has taken its preference for shadowy habitats to the absolute extreme – the dark depths of the Cumaca Caves!

Catfish were first described as dwelling within these Northern Range caves, which are more famous for their oilbirds, in 1926. For many years people believed these cave fish to be a completely different species, named Caecorhamdia urichi, as they were virtually blind, had lost much of their pigmentation and had considerably shorter barbels. However, recent studies suggest that these paler, sightless catfish are simply a ‘troglomorphic’ (cave-adapted) form of Rhamdia, who have invaded the cave and adapted to the unusual conditions. This invasion appears to have happened on at least two separate occasions and deserves further investigation. Indeed, the late Professor Kenny began some preliminary observations which suggested that the cave catfish were remarkably flexible in their traits – for example, when exposed to sunlight, some of their pigmentation would begin to reappear.

Whether cave or river-dwelling, catfish fertilisation occurs externally. This means that the female will lay tiny eggs in the water (each less than 3mm diameter), which the male will then fertilise with his sperm. After just 48 hours these will hatch into fry after which they continue to grow rapidly. Young Rhamdia often have a distinctive dark stripe along their body which fades in the adult fish. If you ever manage to catch a Rhamdia (which is almost impossible using a net, thanks to their preference for hiding in small, dark spaces), chances are it will be a female, as scientists have shown that there tend to be twice as many females as males in the average population.

In the Cumaca Caves, I have only seen small specimens (like in the photo above), but in the rivers adult Rhamdia can reach lengths of nearly half a metre. This makes it the largest catfish species in Trinidad, but nothing in comparison with their Asian relative, the Mekong giant catfish, which can grow to nearly 3 metres long! At the other end of the spectrum, the parasitic ‘candiru’ catfish from the Amazon is just a few centimetres long and is feared for rumours that it occasionally swims up the human urethra causing excruciating pain. However, whether there is truth behind such anecdotes remains a matter of debate.

Several species of Trinidadian catfish are caught for food – including Rhamdia, teta and cascadu. Others are collected to be sold and bred in the pet trade – such as pui pui. However, a much greater threat to the diversity and distribution of our catfish species is the destruction of their riverine habitats, especially in the Northern Range. For example, the Cumaca Cave is situated near to one of the many quarries that are systematically destroying the ecosystem from which we still have so much to learn. I hope that these fascinating fish will be around for a long time to come – who knows what discoveries are still to be made…

May 2015

The wonderful ‘water steps’ of the Turure

This week we visited our sites on the Turure River.

The less-disturbed site is especially beautiful, and marks the start of one of my favourite hikes in Trinidad. Just 30 minutes of hiking beyond our site takes you to the first of multiple ‘water steps’.

These spectacular waterfalls are full of character. Although they vary greatly in their height, width and physical form, they are united by the distinctive calcium carbonate deposits that give them a natural grip – this means that near-vertical surfaces that look impossible to climb, are surprisingly easy and safe to walk up.

At the base of many of the ‘steps’ are clear pools, ideal for bathing – and full of guppies. Indeed, guppies were famously introduced above one of the larger waterfalls by a man named Caryl Haskins back in 1957, as part of a translocation experiment; genetic work shows that this introduced population is still present and spreading down the river nearly 60 years later.

Further up the river, those in the know can locate one particular waterfall that hides a stalactite-filled cave underneath the overhang – even though from the outside it looks much the same as all the others. It takes a leap of faith to duck down underneath and emerge a few seconds later in a small air space under the falls!

This hike is ideal for beginners; the forest and river habitat is picturesque for the entire route, making it one of the best trails in terms of being well rewarded for your efforts! Since we have started monitoring sites on this river as part of BioTIME , I have seen evidence that the quarrying activity further up the valley has increased – for example, the road is now destroyed by heavy quarry trucks making it hard for any non-4×4 vehicles to reach the start point. I hope that despite this increasing pressure on the surrounding valley, the breathtaking upstream stretches of this river will remain untouched.

Species Profile

The manicou crab: a marvellous mountain-dweller

Fish are not the only creatures that turn up in our nets during sampling – we frequently come across freshwater crabs and crayfish too.

It is somewhat surprising that we find crabs at our sites at all, given that they are all quite far from the sea, and tend to be towards the upper parts of the watersheds. However, the mountain, or manicou, crab (Rodriguezus garmanii – formerly placed in the genus Eudaniela) is typically found at between 50-80 metres elevation, and displays several impressive adaptations that allow it enjoy an inland existence.

The first relates to its reproduction. Most species of freshwater crab retain a marine stage to their life cycle by broadcasting their eggs into the water and out to sea, where the larvae develop as part of the zooplankton before migrating back into the rivers. However, the manicou crab is one of only a few species worldwide that no longer produce free-swimming larvae.

Instead, its 200-300 eggs hatch and develop within a pouch formed by the pleopods on the female’s abdomen. This incredible adaptation is the origin of its common name; ‘manicou’ is an Amerindian word for the local opossum which, as a marsupial, also raises its young in a pouch.

I was completely awe-struck the first time we came across a large female at one of our survey sites with a pouch crammed full of moving miniature crabs on her abdomen!

Eventually these babies will venture out into the mountain streams alone, having enjoyed a safe head-start in life. Their diet consists mainly of insects, vegetation and fruit, although as adults they are also known to eat meat – and even each other.

Another adaptation to living in ephemeral mountain streams is a reliance on aerial respiration (thanks to a lung-like brachial chamber); manicou crabs can no longer survive the sustained submersion that is normal for most crabs.

This species, which is native to T&T, Venezuela and the island of Margarita, can grow to around 10cm carapace width, and can weigh up to 250g. The larger individuals are one of three crab species in T&T that are commonly harvested for use in popular local dishes such as ‘crab and dumplings’ and ‘callaloo’. Their non-human predators include birds of prey, and they are even eaten by their namesake – the manicou or opossum. However, judging by my experience handling the adult crabs at our sites, I imagine they put up quite a fight when faced with a predator!

June 2015

Annelise embarks on her next adventure

This month we finished our penultimate session of surveys. We also said a fond farewell to Annelise Randall.

Annelise has been volunteering with us both in the field and in the laboratory over the last few months, and is about to embark on a degree in Bioengineering at Washington State University.

She has been a very useful and enthusiastic member of the team and we wish her all the very best for the future!

Fish school: engaging the public with Trinidad’s freshwater diversity

Every year, the El Socorro Centre for Wildlife Conservation design and present an outreach exhibit at a science fair in Point Fortin, near the south-westerly tip of Trinidad. This year the theme was to be the wildlife of Matura, with an emphasis on the freshwater fish, so the Centre’s founder, Ricardo Meade, asked me to assist.

I was more than happy to get involved, and while Ricardo and his team had the hard task of constructing tanks and catching fish, I set to work illustrating and researching the various species to compile a set of educational posters and labels to accompany the display. This wasn’t hard as most of the species were those that we commonly come across on our BioTIME surveys.

Then, on the evening of the 30th May, we made the long journey southwards to the exhibition site, along with two truckloads of display equipment and bags, tanks and cages full of native animals. We worked until late into the night, setting up the tanks and releasing the fish from their transport bags into the aquaria. Ricardo had managed to collect an impressive variety of species, with star specimens including the cutlass fish (Gymnotus carapo) and two young caiman (Caiman crocodilus). However, there was one species in particular that he had searched in vain for – the mysterious zangee, or ‘snake eel’ (Synbranchus marmoratus).

These fish can be found in quite urban settings, as well as mountain streams– so along with another volunteer, Wayne, I headed off to the local drainage ditch to see if we might at least find something worth adding to the display. By now it was 10pm at night. The first fish we came across were, of course, shoals and shoals of guppies (Poecilia reticulata), living up to their local name ‘drain fish’. We took a few scoops for the display. Next we found a gathering of adult rivulus (Aneblepsoides hartii). These darted away quickly once we shone our light on them, but we managed to capture a handful. Just as we were about to turn back, we spotted a yellowy-brown head poking through the concrete in the drain – a zangee! Of course, it retracted into the crevice as we approached, so Wayne decided to prize open the concrete slab in the hope of revealing it again. On levering away the concrete, we were astonished to find an extensive tunnel system running though the mud behind the slab, which wasn’t even underwater (they can breathe in air). But no zangee.

By now the water in the ditch was brown with sediment, so we were blindly sweeping our net through it, feeling certain that the fish must be in there somewhere. Finally we noticed that the eel-like fish had wriggled upstream and was quite visible just a few metres away in the clearer water. With a little coordination we succeeded in securing our zangee, which was a nice size of around 30cm (they can reach 1.5m).

We released our finds into their display aquaria to settle in overnight, and went to bed feeling very pleased with ourselves.

The next day we had just enough time to finish adding the posters to the display and making some last-minute adjustments to the lighting before coachloads of school children began to arrive. My job was to guide them around the fish display, answering their questions and filling their heads with interesting facts.

Many were amazed to hear that all of these species were found in Trinidadian rivers – not from other countries, and not from the sea. None were aware that the cutlass fish generates an electric current for navigation and communication in swampy waters, and most had assumed that the long slithery zangee was a snake, rather than a fish. I was very happy to be able to show them a live specimen of this legendary species in particular.

The older students enjoyed hearing about the guppy’s international fame as a model species in biology, and for many of the younger pupils it was probably the first time they had laid eyes on any of the species on display or even considered what swims below the surface of the country’s rivers and streams.

By rough calculations, by the end of the day I had enthused about fish to nearly 1000 students of ages 5-15 years; my legs were tired and my throat was completely dry. It was fun but exhausting, and I am hopeful that by introducing these kids to the wildlife that share their streams, they may think twice about leaving garbage by the riverbank after a lime – or, even better, some of them might decide that freshwater fish are worth learning more about, and even embark on a career in biology!

July 2015

The final sampling session begins!

With mixed emotions of sadness and satisfaction, this month we began our final sampling session for the BioTIME project. It feels strange to be visiting the sites for the last time (for a while at least), and exciting to think that soon our five-year dataset will be complete.

At our Turure site, we were reminded that our sites are subject to natural as well as human disturbances: a large tree had fallen across the stream, right in the middle of our sampling stretch! Thankfully Raj was able to cut a route through the vegetation so that we could access the other side – but it was still quite a challenge to transport the equipment through.

Over time, it will decompose and wash away, but in the meantime it is providing habitat, not just for the birds, insects, epiphytes and fungi that continue to use the fallen tree, but now also for the aquatic creatures that may be using the underwater vegetation as a safe place to hide or forage.

Once finally on the other side, we were greeted by a stunning golden-headed manakin, as well as the usual picturesque scene, reminding us what a beautiful site the upper Turure is, and how lucky we have been to have had an excuse to spend time here over the last 5 years.

October 2015

Fieldwork finale!

In August we completed the twentieth and final session of surveys of our Northern Range sites! It felt strange to visit the places that have become so familiar for the last time in a while, but also very satisfying to feel that the five year project is nearly complete.

It was a fun session, as visiting researcher Miguel Barbosa joined us from Scotland. Miguel has studied guppies for 10 years, yet this was his first experience seeing them in the wild. By the end I think he had probably seen enough to last a lifetime…

Now we can start to look at the huge amount of data that we have accumulated, and see what we can learn from it!

November 2015

This week I am excited to announce that our first paper from the Trinidad BioTIME project has been published in the journal Ecology and Evolution.

It describes differences between the fish communities at disturbed and undisturbed sites, which we detected at multiple levels of community properties.

Read a summary here, or check out the article itself here.